Peter Cohen of Santa Barbara, California, has made feline infectious peritonitis his personal cause, having lost two kittens to the dread disease. He now has a third, Smokey, who is a survivor.

Cohen’s first experience with FIP, a fatal viral disease in young cats, was in 2012 when he adopted a pair of litter mates, Peanut and Butter. Butter thrived but Peanut failed. Diagnosed with the untreatable disease, Peanut was euthanized.

Another Loss—and Hope

In 2016 Cohen once again adopted a pair of littermates, Vanilla and Miss Bean. Miss Bean was the runt of the litter and never seemed to catch up to her sister. Her veterinarian confirmed Peter’s fears with a diagnosis of FIP.

With broken heart, Cohen planned to euthanize her even as he began searching the web for support groups. Through one of them he discovered that University of California Davis School of Veterinary Medicine was conducting a clinical trial for the drug GC376.

He immediately called and spoke with Niels Pedersen, DVM, who was heading the trial. There was room for one more cat. If Peter could get Miss Bean there the next day, and if she met the protocol, she would be accepted. Cohen did not hesitate. Miss Bean began the program of injections.

In this first trial, kittens were treated onsite for two weeks, until they rallied, and then were sent home to continue the twice-daily injections for the rest of the course. Miss Bean was at UCD for four weeks but sadly did not respond and was euthanized.

Getting the Word Out

During Miss Bean’s battle, Cohen launched ZenByCat.org, a nonprofit dedicated to raising funds for FIP research. He blogged about Miss Bean and strove to raise awareness and donations through her story.

Cohen continued to be involved with online support groups and, a week after losing Miss Bean, saw a post on an FIP Facebook page from a couple in Long Beach, California, desperately seeking help. Their kitten, Smokey, had been diagnosed with FIP and had been accepted into the UCD clinical trial, but logistically it was too far for them to travel.

Cohen continued to be involved with online support groups and, a week after losing Miss Bean, saw a post on an FIP Facebook page from a couple in Long Beach, California, desperately seeking help. Their kitten, Smokey, had been diagnosed with FIP and had been accepted into the UCD clinical trial, but logistically it was too far for them to travel.

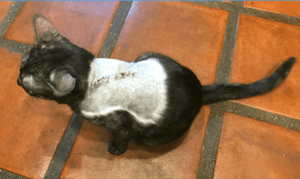

Cohen contacted them and all agreed that he should adopt Smokey. He drove down to pick the kitten up and the next morning drove him to UCD. Smokey was one of the last to be accepted into the trial.

Treatment

Dr. Pedersen knew from previous testing that GC376 cured FIP in many cats. This trial was about establishing dosage and length of treatment. When Smokey entered the trial, dosage had been steadily increased and treatment lengthened to nine weeks but cats were still dying. By the end of the trial, they found that 12 weeks was the magic number. Five out of the original 20 survived, including Smokey. (In the second trial, 22 cats out of 25 were cured.)

During those 12 weeks, Smokey endured 168 painful injections. Deep scars developed along his upper back and shoulders that had the potential  of developing feline injection site sarcoma (FISS).

of developing feline injection site sarcoma (FISS).

The risk of FISS is low, but Dr. Pedersen recommended having the scars surgically removed. He did not want to cloud the trial results and thought Smokey would do better recovering from surgery than potentially having to deal with cancer down the road. When he was 16 months old, Smokey underwent surgery.

Now 3 1/2 years old, Smokey is a handsome and healthy cat. No more need for special checkups; he now has only yearly exams and blood work.

Making Treatment Affordable

At this time, the cost to treat FIP is a barrier for the average cat owner. The key to affordable treatment lies in funding for continued research.

Curing FIP has become Cohen’s mission. His nonprofit, ZenByCat.org, includes the FIP Warriors page, with information and links to resources as well as a donation button.

“Just $10 a month–two cups of coffee–won’t break your budget,” Cohen says. “Zen By Cat’s goal is to have 5,000 people sign up for this [monthly giving], which would result in $50k a month!”

Imagine a world free of FIP, free of the stress and heartache when a kitten is diagnosed or dies, and instead full of happy, healthy kittens.

This article was reviewed/edited by board-certified veterinary behaviorist Dr. Kenneth Martin and/or veterinary technician specialist in behavior Debbie Martin, LVT.